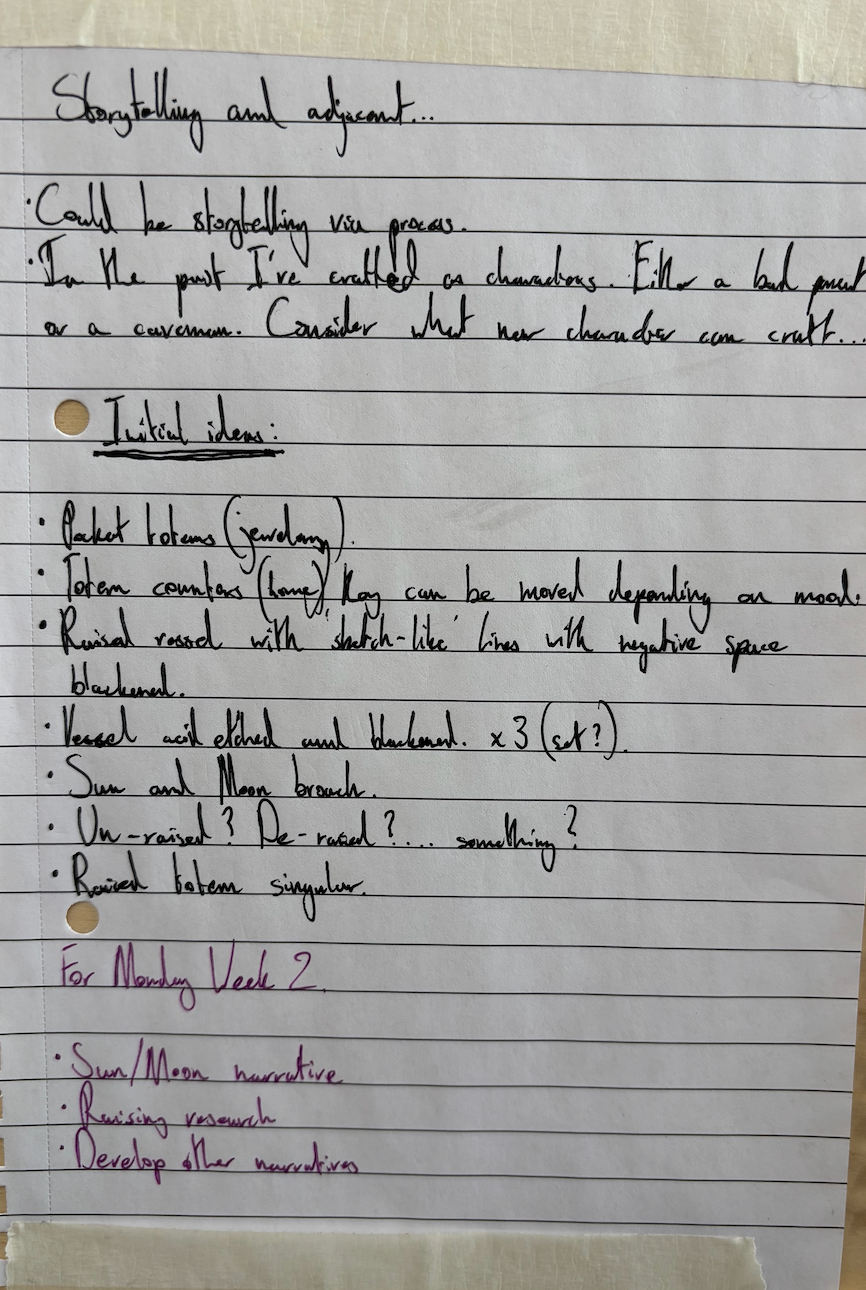

Heading into this project, I wanted to focus on storytelling through objects. Below are supporting documents analysing how I could involve stories within my pieces as well as books that affected my research. As I mentioned in my statement of intent, I was particularly interested with personifying the sun and moon and looked at how other cultures saw the two heavenly bodies. In addition, in the previous term I've gained feedback that stated that I should include more personal narratives in my work.

I researched the significance of the moon and the sun to get general insight of how they were perceived through time along various media. My favourite piece I found being the poem, The Tale of the Dead princess and the Seven Knights by Alexander Pushkin, where the moon is personified as a protector and overseer of the night.

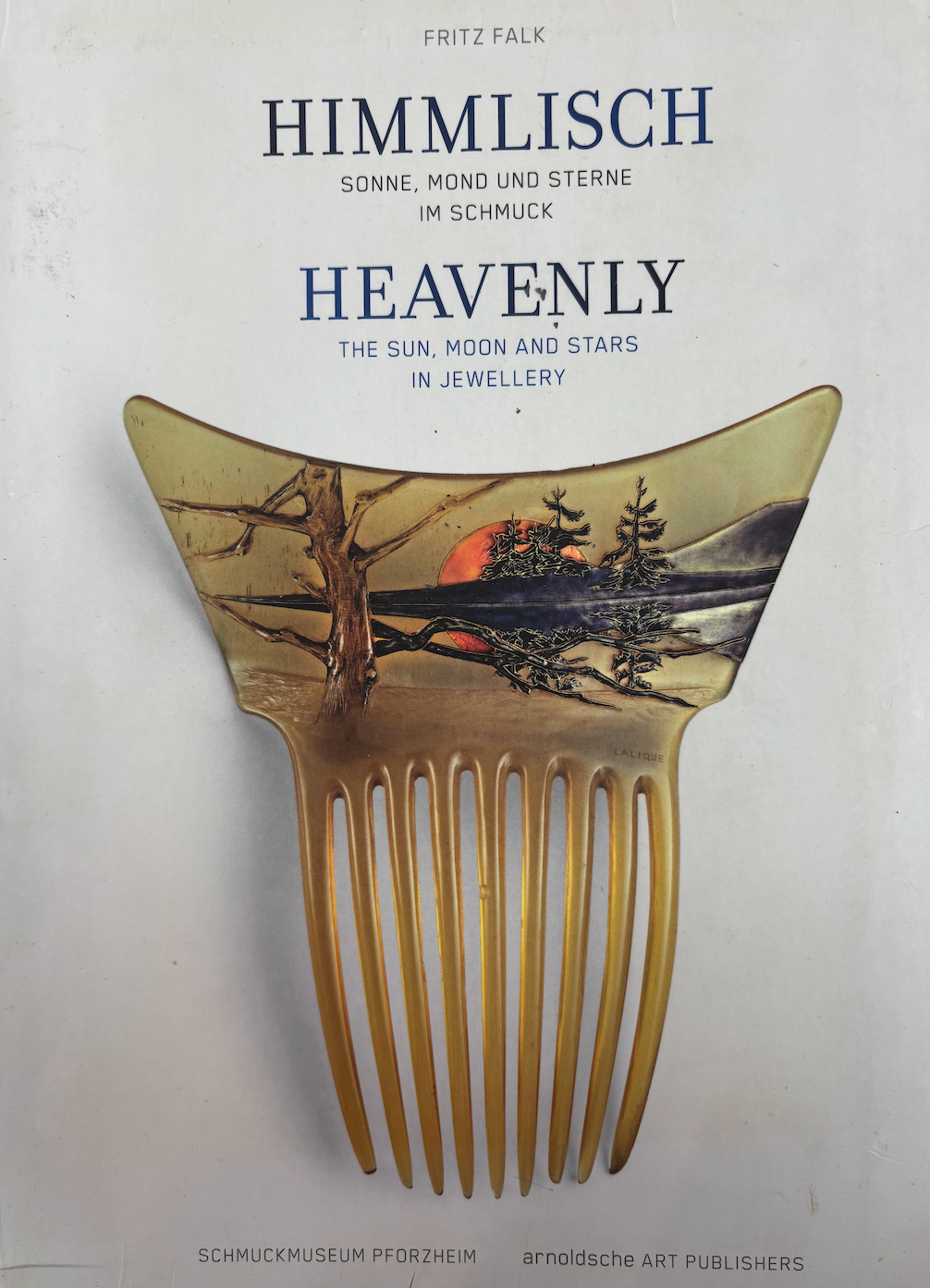

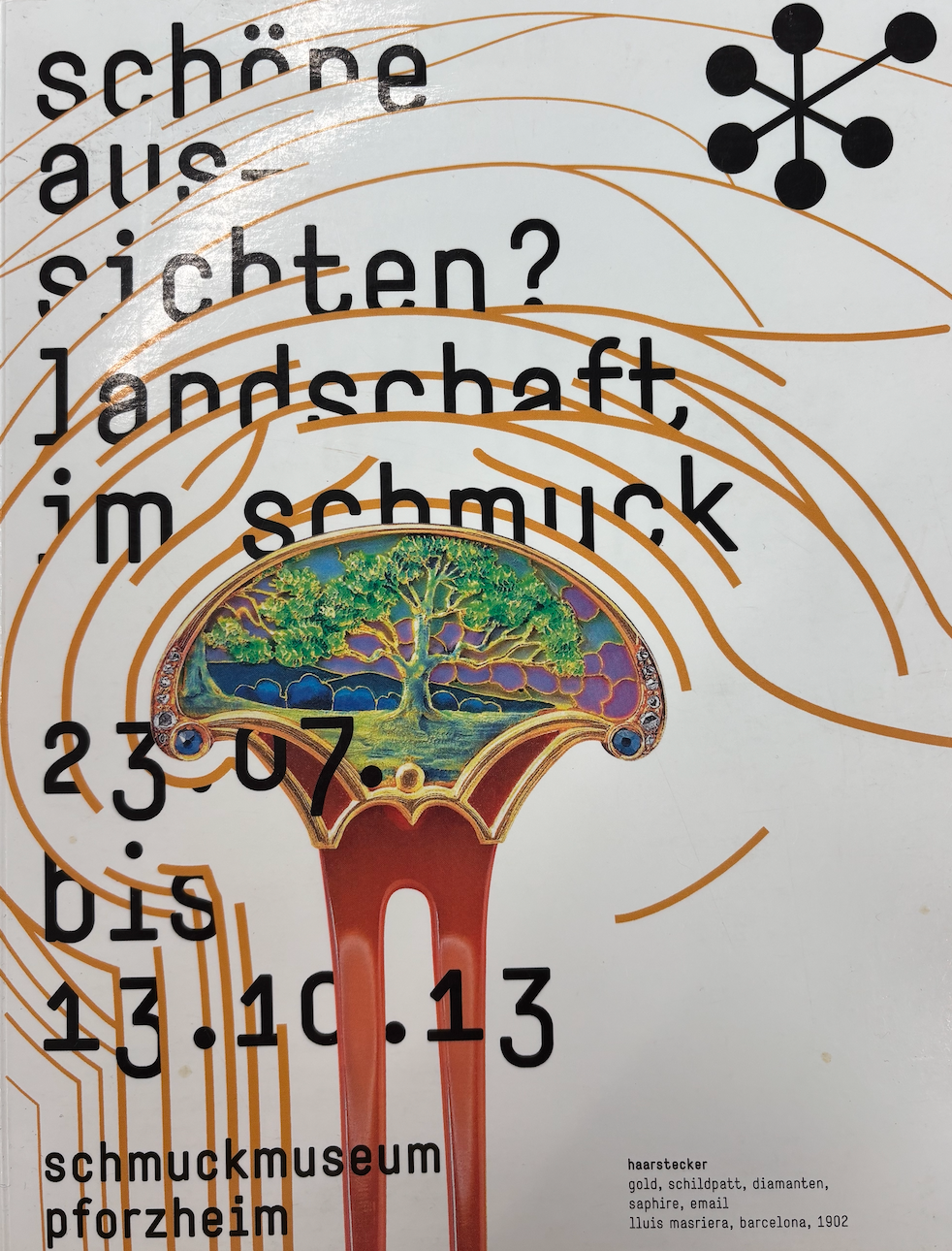

These books helped me with the cultural significance of the moon and sun, across a wide spectrum of religions and regions well as developing my understanding of object value.

The way that gods and stories were imbued into the objects in these books made me rethink the word, 'vessel'.

The 'Nebra Sky Disc' was particularly interesting. It's not a container by traditional means yet, remains a vessel. It's a device imbued with something we don't understand in present day.

I think the age of it provides an illusion of the object having otherworldly properties.

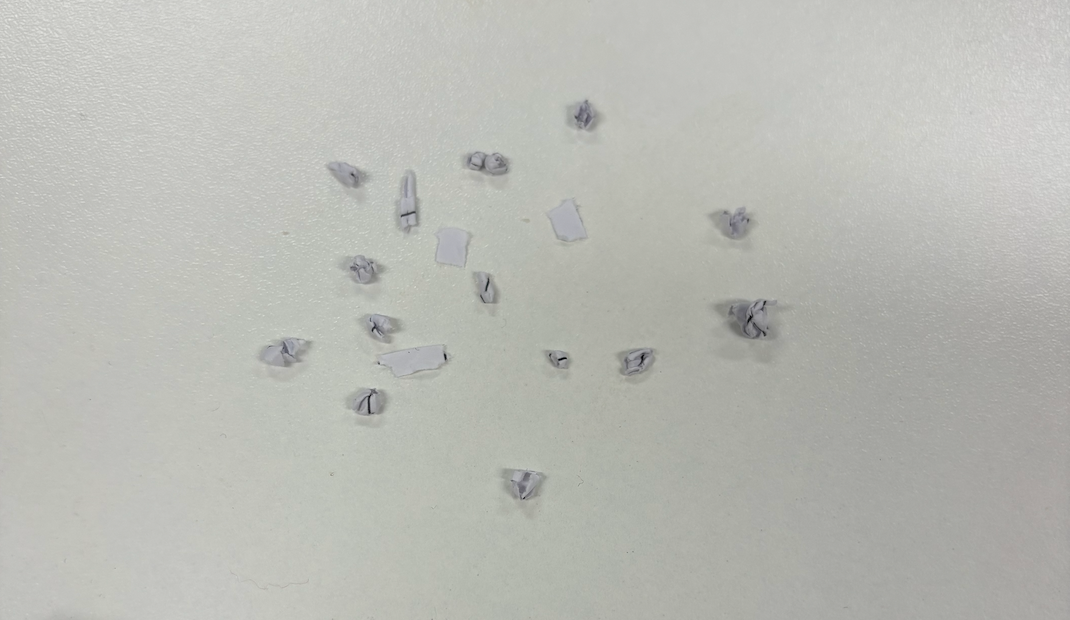

I looked back and old work wiith the mindset of creating a wider range of pieces, I rearranged a selection of my previous vessels to see how my work could potentially be displayed.

If I were to remove my contextual knowledge of the pieces and just view them as a collection, I would see them as archeological finds.

The pieces above look ancient but of unknown origin, there is an underlaying theme tying them together, implying cultural similarities. Yet, their significance remains ambiguous.

Relaying with a tutor, we established they are part of a museum exhibition, items from a new past. This peaked my interest, it seemed very 'Indiana Jones'. For this project, I won't be raising or making - the objects are discovered.

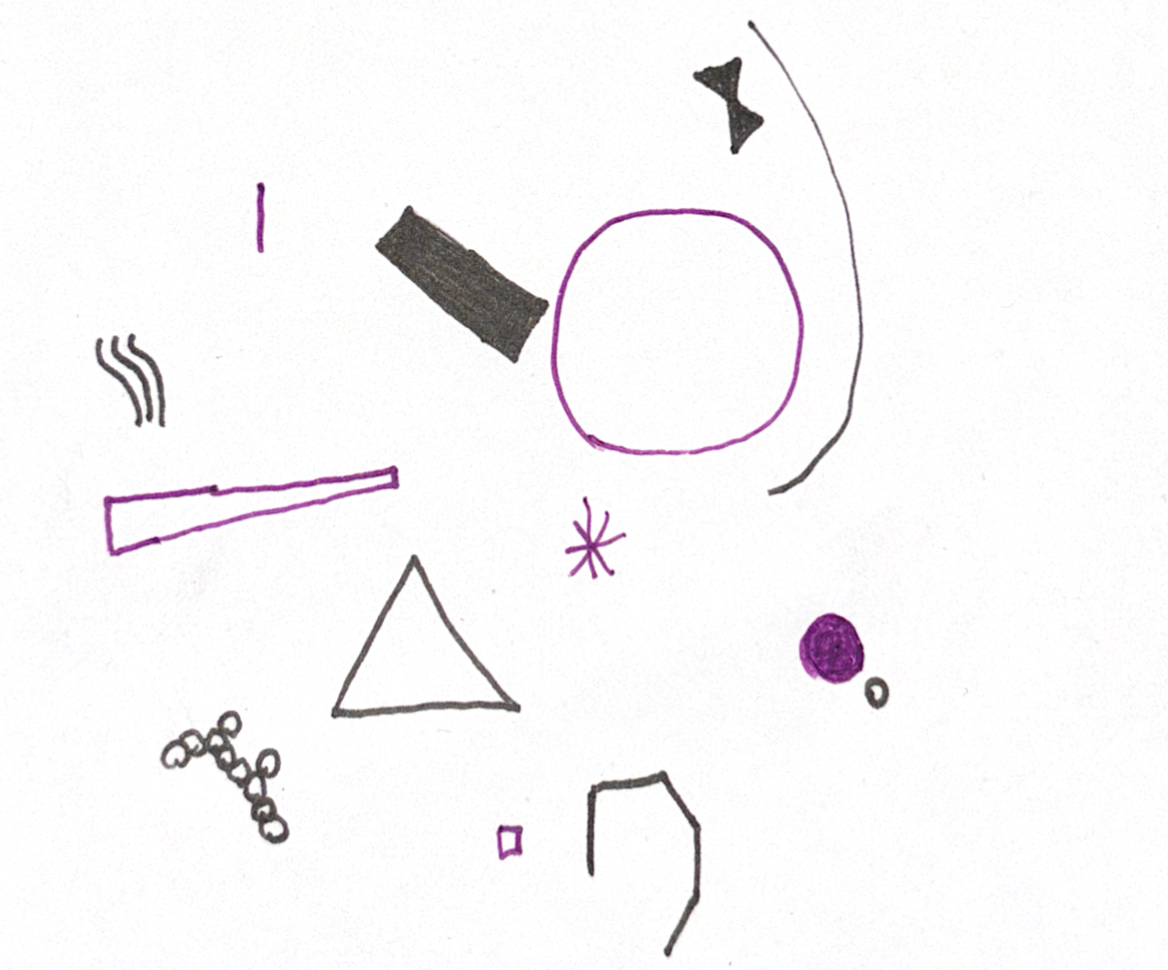

I replicated the 'scatter' layout in paper - although the paper was too uniform, the organised mess had a positive impact on the continuity of the subjects; taking into account the ruling lines from the top image and the printed parts of the bottom image, there is a subtle connection between each one of them as well as the more obvious, material one.

The range of something recontextualises its story. The images below use some of the same subjects but differ in personality, the first picture depicting opposites whereas, the other creates an understanding to what the shapes mean.

I feel like making a wide collection would add exposition.

The specification now was to create a series of artefacts, imbued with narrative - world building off of one another. To visualise this on a small scale, I created runes:

The rune shapes could coexist with the final object in some way, adding depth to the story they occupy.

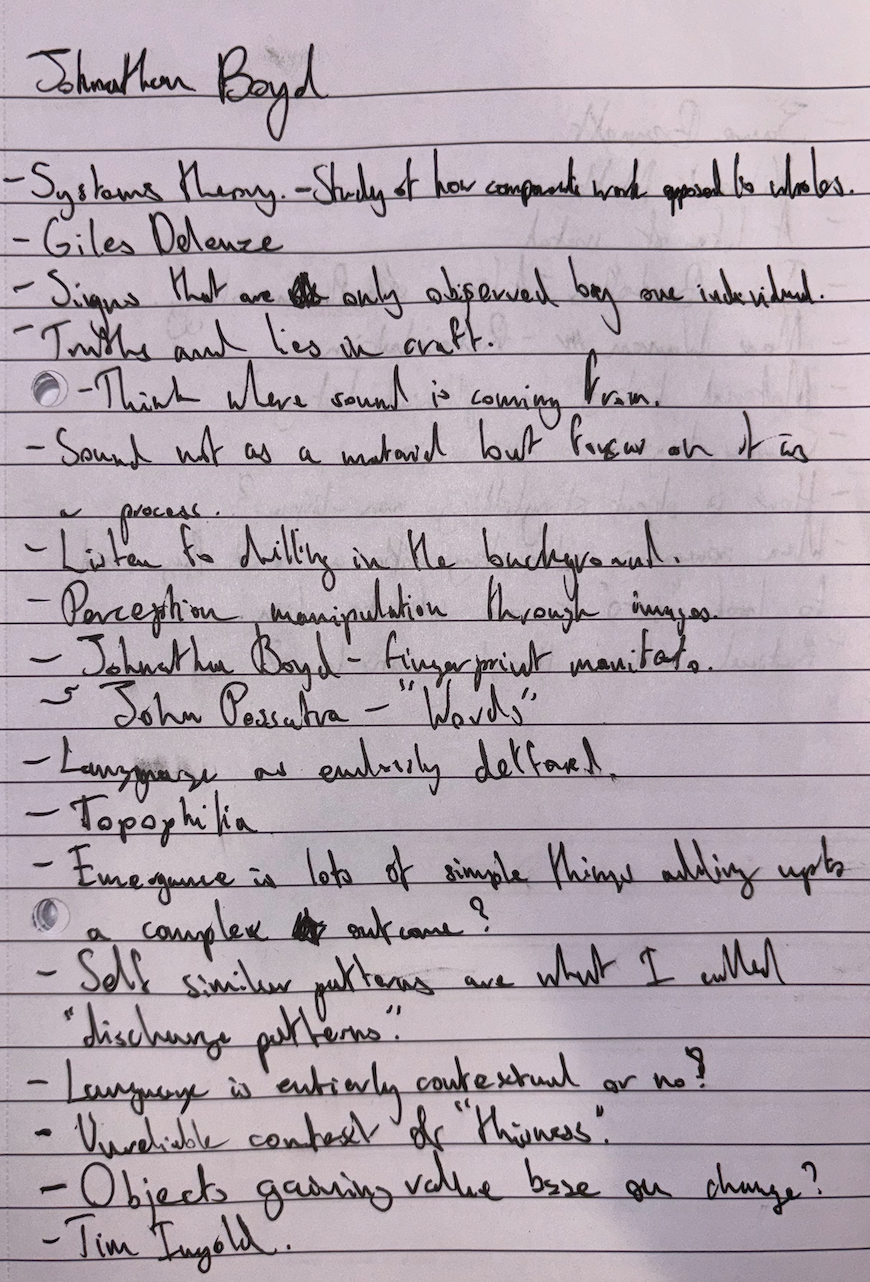

In a talk with Johnathan Boyd, he bought up systems theory; the idea of everything being made up of connecting parts, each part having an effect on the whole. Systems theory allows us to navigate how this 'whole' operates based on the relationships between components.

With that in mind, any museum artefact you see can be considered a 'component' of a greater history. These artefacts hint at what the past was like but, don't disclose the whole context.

I like the idea of 'isolating history', having an understanding of something strictly through one type of artefact. For example, if the Nefertiti Bust was the only surviving mark of ancient Egypt, there would be nothing to explain the headpiece, the proportions, the colours used. If truly nothing else was discovered, there would be no way of even confirming that the large, black cylinder is even a headpiece.

Archeological objects gain relevance through other finds that are linked to the greater picture, like bones or art of a different media. The pieces I'm producing should all be made for the same reason and be labelled / titled with its vague purpose. The pieces I'm producing are isolated historically, they are vague in form to not reveal too much.

I want the viewer to question the pieces and wonder where they came from and how the objects were used. The idea of 'suspending an audience in disbelief'. I want the viewer to see a copper vessel and make themselves believe that it is a 'prayer tool' of the past. Although not the focal point, I see there's a motif of the truths and lies of craft in my work - could be developed.

Below are some more notes from the Johnathan Boyd talk that may be relevant later:

In my tutorial with Johnathan Boyd, when I told him about the archival object besides my final piece(s), he told me that I should do a book. I brainstormed a good way that I could do a book whilst maintaining the illusion of the object not being made by me and, conveying with my tutor, we came up with two options:

- Speculate about how the object was made. Write as an unreliable narrator and guesstimate how the object was made and where it originated...

- Write in a made-up language, use the runes that I haphazardly put together and act if they were a typeface, whilst having obscure images plaguing the pages. Just nonsensical. It would also be developing on the narrative like it's an ancient tome and it's illegible but it exists and it explains the object just in a way that we don't really understand. Clues.

We continued about how this opens up my work to the possibility of all pieces being part of a system. If they're all theoretically 'found' by me and I either make educated guesses as to their origin or their origin remains mostly ambiguous, then each new piece I make could be just another part of a fake history. Yet, I later decided that having the objects 'system-less' would be better for my narrative and allowed the possibility of every object I make from this point onwards add to the system of these pieces; world building much more effectively.

To get into character while raising, I took a trip to the Peak District to separate myself from technology for a bit and take in nature and get into a primitive mindset. Without distractions, only raising resided in my head.

When talking to David Ray about my essay from the previous term, he mentioned how 'sloppy craft' can be challenged. The word 'sloppy' having negative connotations. From this, I took that 'sloppy' craft is always 'sloppy' to give character to the object. Much as brutalist objects have a certain seriousness to them, sloppy objects are more fantastical. I think sloppiness could also indicate age; purposeful sloppiness is often in historical props, battle damaged armour, burnt flags, worn rags etc. I could use this sloppiness to further indicate a lost time period.

I looked at Jonathan Boyd's 'An Endless Rant On Craft' from 2012, to get an idea for other ways to include words in make without having a secondary written piece besides my objects. Here, the artist creates an explicit narrative with an object by having the user read it, the piece essentially speaking out to the viewer.

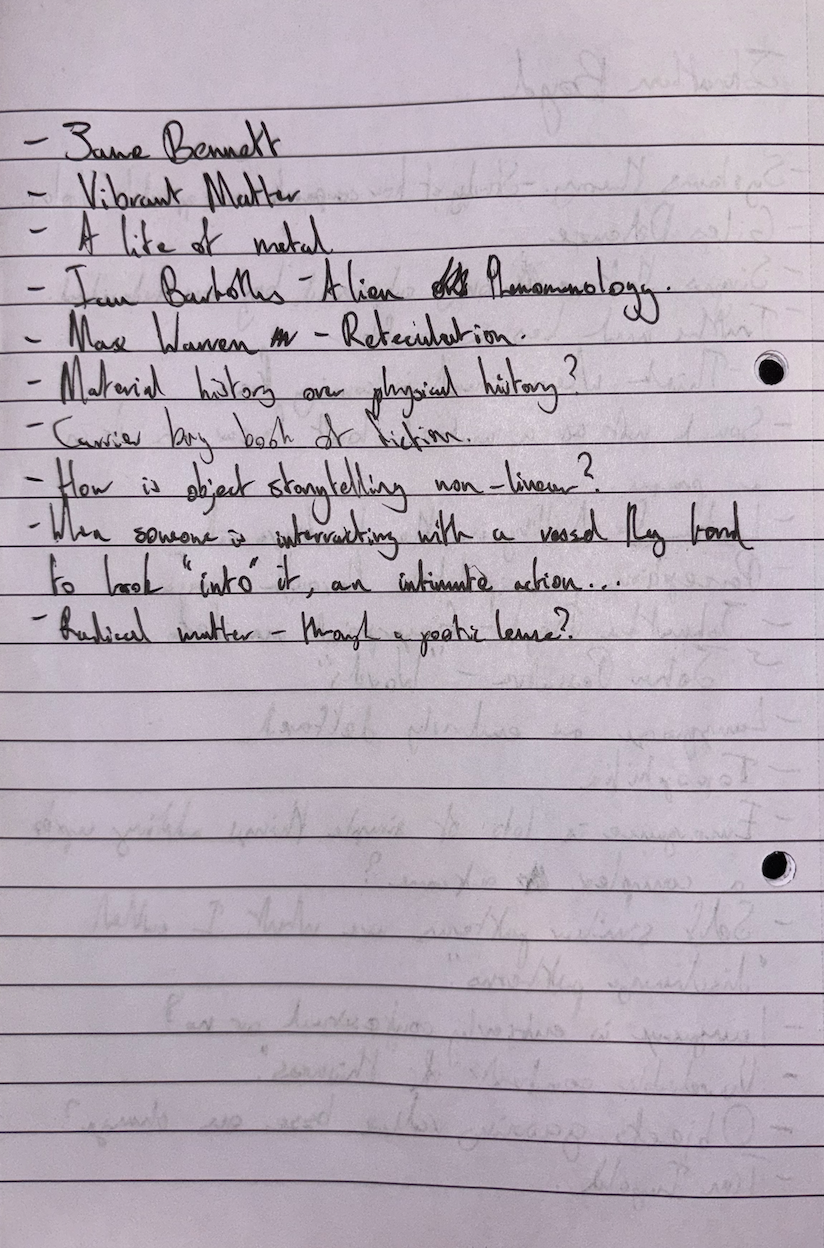

Jane Bennett's 'Vibrant Matter' was a new addition to my theories supporting my ways of craft. The book touches on the way nonhuman forces affect events.

Alien Phenomenology, Ian Bogost, was another book that developed on my understanding of Object Oriented Ontology pushing me to perceive my objects from an outsiders perspective, working them out based on what they show me about themselves. This also related to something Johnathan Boyd said during his lecture that caught me off guard; 'is object storytelling linear?'

I suppose in my case, the process wasn't linear. There was several moments where I went back to what I did, what mistakes I made etc. and I had to figure out what this meant to the objects. Other theorists that were key to my research for this were Roland Barthes and Erik Erickson, their influence on my way of working is outlined in my previous essay project.

Another inspiration behind the completely fictional world I'm presenting was Damien Hirst's 'Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable'. This was a series of objects made by the artists and presented as artefacts found in a shipwreck.

This is the level of unreliable narration that I aspired to throughout my make.

In terms of form, I was influenced by Barbara Amstutz (left) and Ismael Conde-Ruiz (right). Their vessels, that I found out through the book 'Silver Triennial International', intrigued me because of their sharp edges. The pieces seem like they're folded rather than raised.

Grayson Perry's 'The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman' was also of great significance to this project. The book went over artists' projects that are grounded in storytelling. An important quote from the book that informed my make being; 'Part of my role as an artist is similar to that of a shaman or witch doctor. I dress up, I tell stories, give things meaning and make them a bit more significant Like religion this is not a rational process, I use my intuition. Sometimes our very human desire for meaning can get in the way of having a good experience of the world...'

Unpacking that quote, I agree with he first half, even with this project I wasn't making as myself, just as I have done in the past, when I make I'm in the shoes of whoever I need to be to complete the task, the story this develops adds significance to even the most mundane piece. I often, especially with this project, stick to my intuition and make what the metal wants to become when raising it. However, I question the latter half; in the sense of this project, the human desire to know more is key to get as much out of the object as possible. My pieces are to be questioned.

Below are some highlights of the book, objects that to me symbolise an alternate history. They look like primordial finds, yet are purely based in lies:

The objects below are good at asking questions. If seen in a museum without the context of the artist, one would be intrigued of the origin of the pieces. Grayson Perry is a talented storyteller as the objects are just unbelievable enough, they seem like they could exist with a historical origin, yet the viewer knows the truth. Pieces like the middle one support their mythos with the title, giving contextual signified information. Manipulation.

The art book, 'The Art of Diablo' outlines the designers ethos when designing creatures. The second rule of character design mission statement being '... the character's design must tell a story.' My objects can be analysed as characters to an extent, they're newly made copper vessels, playing a part.

Returning to Barthes' work on Mythologies, I summarised my vessels in the correct terminology.

The signifier is the sound representing the object, I'm this case, ritual / pouring vessels. This selection of words may signify something like a teapot when spoken in isolation. The teapot being a vessel, used to pour tea during the morning ritual of breakfast.

The sign that accompanies the signifier is the physical form that my pouring vessels take. The form dictates how we interpret the words ritual and pouring, developing a story in the audiences mind. The further contextual clues you get from details in the objects; like their wayward bases and circular markings along with their implied meanings, can be noted as secondary signified which develop a narrative to surround the pieces, the myth.